Macro Focus – A Fiscal Turning Point in The U.K.?

UK markets had been eagerly anticipating it: yesterday, Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves presented her budget for the coming year. This budget, seen as a potential year-end catalyst, was in the spotlight, with investors hanging on every decision from the Chancellor. Following the announcement, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the body responsible for the country’s economic and fiscal projections, updated its outlook for the UK’s fiscal and economic trajectory.

Context

Public debt now stands at nearly 98% of GDP—three times higher than at the start of the century. The growing weight of interest payments is increasingly burdening the budget, with the deficit estimated at 4.5% in 2024. This year’s deficit could reach 5.0% of GDP, as the OBR’s initial forecasts have been repeatedly revised upward. Against this backdrop, the government has announced cost-saving measures aimed at restoring the health of the UK’s public finances.

Inflation remains persistent, prompting the Bank of England to keep interest rates high to contain price pressures. For 2025, inflation is expected to average 3.5%, 0.9 percentage points above the advanced-economy average. In early November, the Bank maintained its policy rate at 4.0% amid unprecedented division: 4 of the 9 voting members advocated for a 25-basis-point cut.

At the same time, the economy is struggling to regain momentum. A rising savings rate illustrates growing household caution about the economic outlook. Consequently, the Bank of England may continue its gradual monetary-easing strategy despite lingering inflationary pressures, aiming to avoid an excessive slowdown in activity while containing fiscal-slippage risks.

Announcements

The Chancellor outlined a plan to rebalance public finances through significant fiscal expansion affecting all income categories. In the short term, the deficit is expected to worsen due to higher public spending, which—according to the government—would later be offset by increased fiscal revenues within 2 to 4 years. Budget projections through 2030 anticipate an £11 billion increase in spending and a £26 billion increase in revenues directly linked to the new policy measures.

The stated objective is to restore the primary budget balance by 2029–2030. The OBR forecasts a shift from a primary deficit of 1.5% of GDP in 2024–2025 to a surplus of 1.4% in 2030–2031. The government is therefore walking a fine line: stimulating growth and consumption through immediate spending increases while accepting a weakening of medium- and long-term growth potential.

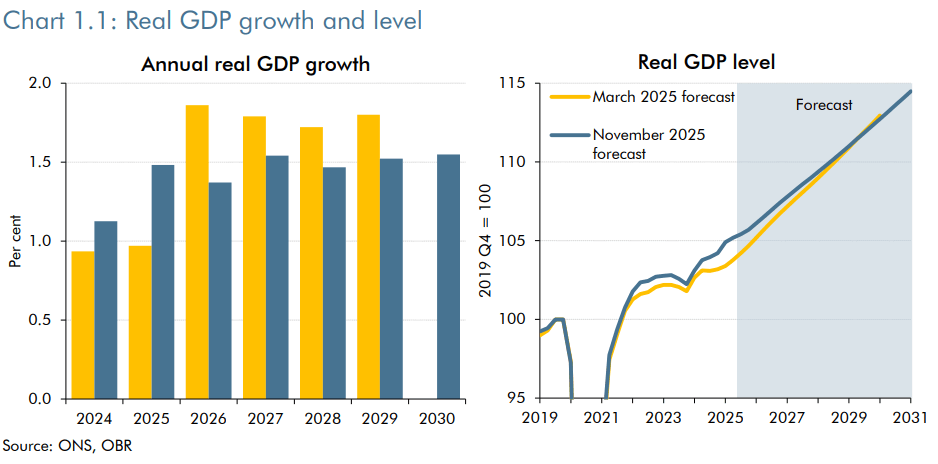

The effects are immediate: short-term economic projections—measured through real GDP growth—have been revised upward by 0.5 percentage points for 2025. The cost of this strategy becomes apparent in subsequent years, as the large fiscal package is gradually rolled out.

Real GDP is now expected to be higher than previously anticipated in 2025, before being revised downward from 2026 onward. Source: Haver Analytics, OBR

Breakdown of Measures

Increase in Public Spending: +£11bn in 2029–2030

- Social spending: +£9bn

- Reversal of previously announced cuts to winter heating allowances and health-related benefits (costing £7bn in 2029–2030).

- Removal of the two-child limit for Universal Credit (costing £2–3bn by 2029–2030).

- Other expenditures: +£2bn in 2029–2030 (but +£10bn over 2027–2028).

Increase in Tax Revenues: +£26bn in 2029–2030

- Freezing of tax thresholds from 2028–2029: +£8bn

- Higher national insurance contributions: +£4.7bn

- Higher taxes on dividends and capital gains: +£2.1bn

- Introduction of a road-usage levy for electric and hybrid vehicles: +£1.4bn

- Reduction in deductible corporate depreciation allowances: +£1.5bn

- Gambling tax reform: +£1.1bn

UK Bond Market Dynamics

UK Yield Curve Developments

A year ago, the UK yield curve was inverted, with short-term rates exceeding long-term rates. Since then, the curve has normalized as the Bank of England cut rates multiple times—last February, May, and July. One-year yields have declined to 3.73% from 4.55% a year earlier. Conversely, the long end of the curve (maturities beyond 8 years, notably the 10-, 20-, and 30-year segments) has steepened markedly.

This surge in long-term yields reflects rising term premiums—additional compensation demanded by investors for holding longer-dated securities. The higher term premium is driven by:

- Persistently high inflation (3.6% year-on-year in October), even as expectations for future rate cuts grow

- Uncertainty surrounding the country’s fiscal trajectory

- Structural changes in demand for gilts

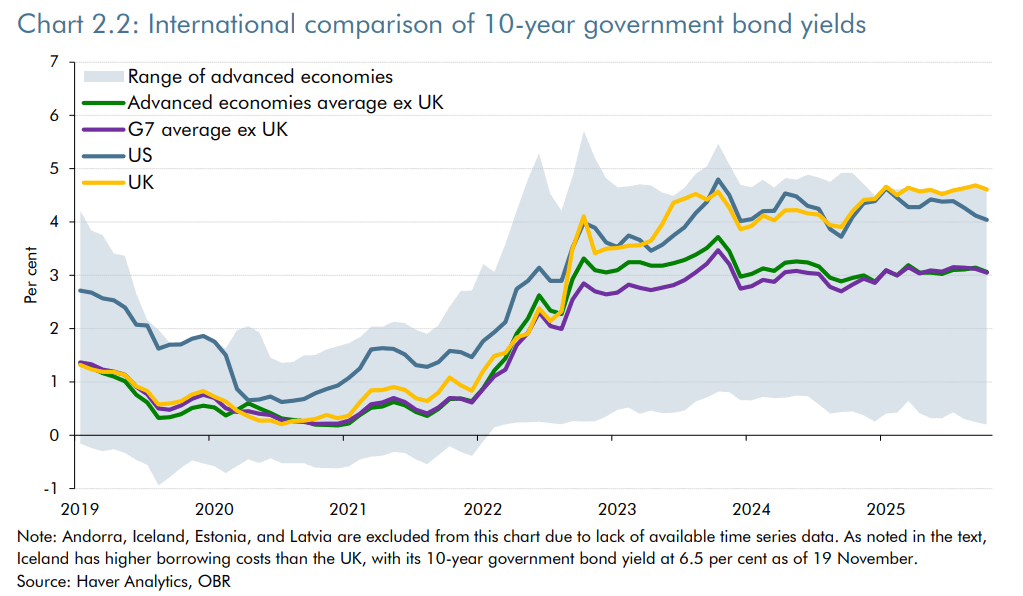

UK 10-year yields have climbed steadily throughout the year. Source: Haver Analytics, OBR

Shifts in Bond Demand Structure

Historically, domestic institutional demand for gilts was strong, supported by two systemic actors: UK pension funds and the Bank of England. Demand from both has weakened over time, disrupting the balance between supply and demand.

For the Bank of England, the decline stems from a strategic shift. The BoE has ended its Quantitative Easing programme (through structural participation in Treasury auctions) and has moved to Quantitative Tightening—reducing its balance sheet by not reinvesting maturing bonds. This QT policy indirectly puts upward pressure on yields by increasing gilt supply to the market.

This decline in domestic demand must be replaced by foreign investors, who typically demand higher term premiums, especially to hedge currency risk. The 2025 Fiscal Risks and Sustainability Report (FRS) anticipates a 0.8-percentage-point rise in term premiums in the coming years due to weak domestic demand for UK sovereign debt.

These structural shifts come amid significant upward pressure on the long end of the gilt curve. UK 10-year yields are near 4.5%, one of the highest levels among OECD economies. In this environment, the Bank of England has decided to slow the pace of Quantitative Tightening to curb the rapid rise in yields.

Shifts in Bond Supply Structure

The Debt Management Office (DMO), responsible for managing and structuring UK public debt, has drastically reshaped its strategy over the past decade. Ten years ago, demand for duration was much stronger than it is today; since then, markets have increasingly favored short-dated maturities. The average maturity of new issuance is now about 10 years, compared with 20 years in 2015–2016. Today, 44% of new issuance is concentrated in short-term maturities—20 percentage points more than in 2015–2016.

This shift mainly reflects evolving investment strategies among UK pension funds, which now seek more flexibility and less exposure to duration risk.

Consequences of This Shift

- Lower refinancing costs for the government, as short-term rates are mechanically lower than long-term rates. The surge in long-term yields is therefore partially offset by a concentration of issuance at the short end (a trend also observed in the United States, where Scott Bessent has made this approach central to US Treasury strategy).

- Greater risk of strain at auctions, with a heavy schedule of short-term issuances. As the average maturity declines, refinancing needs become more frequent, requiring structurally strong and stable demand for short-term gilts.

- Higher volatility of the effective interest rate on public debt: longer average maturities help stabilize future payments, but this is no longer the case. With today’s maturity profile, a 1-percentage-point shock to interest rates in 2025–2026 would increase interest payments by £17bn in 2030–2031.

- Greater dependence on the Bank of England, as its policy rate directly affects the shortest maturities.

As a result, the Bank of England’s two traditional mandates—employment stability and inflation control—are no longer the sole determinants of its policy-rate decisions. The Bank must now also consider, implicitly, the sustainability of the fiscal trajectory to avoid short- and medium-term financial imbalances.

This evolution, also visible in the United States, revives concerns about the true independence of central banks from governments. Ultimately, it contributes to further increases in local term premiums…

Alexandre Germann, Market Analyst, XTB

The material on this page does not constitute financial advice and does not take into account your level of understanding, investment objectives, financial situation or any other specific needs. All information provided, including opinions, market research, mathematical results and technical analyzes published on the Website or transmitted To you by other means, it is provided for information purposes only and should in no way be construed as an offer or solicitation for a transaction in any financial instrument, nor should the information provided be construed as advice of a legal or financial nature on which any investment decisions you make should be based exclusively To your level of understanding, investment objectives, financial situation, or other specific needs, any decision to act on the information published on the Website or sent to you by other means is entirely at your own risk if you In doubt or unsure about your understanding of a particular product, instrument, service or transaction, you should seek professional or legal advice before trading. Investing in CFDs carries a high level of risk, as they are leveraged products and have small movements Often the market can result in much larger movements in the value of your investment, and this can work against you or in your favor. Please ensure you fully understand the risks involved, taking into account investments objectives and level of experience, before trading and, if necessary, seek independent advice.